GUIDE

![GUIDE]()

![GUIDE]()

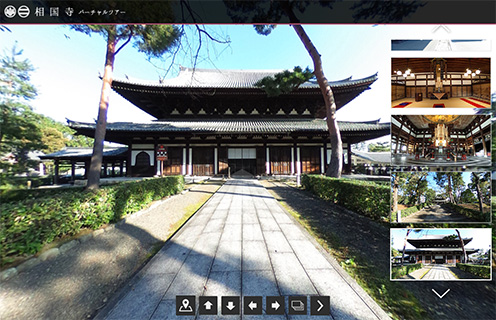

The premises will be introduced through a 360-degree virtual tour

which feels just like the real thing.

01

総門Somon

Lined up alongside the main gate of Shokoku-ji is the Choku-mon, the imperial envoy gate. Whereas the main gate was made for everyday use, the imperial envoy gate was meant to be opened only on special occasions. It was first built in the area of Muromachi-dori and Ichijo-dori. It was rebuilt in the third month of Bunsho 1 (1466), and during the ten following days, Yoshimasa passed through the gate for the first time. After this, there were many losses due to fire (such as the Great Tenmei Fire) and subsequent rebuildings; the current building having been completed in 1797 by the 113th high priest Baiso. In 2007, it was designated a Tangible Cultural Property by the Kyoto prefectural government.

02

勅使門Chokushimon

There are many Zen temples with main gates in front and another gate alongside it. This imperial envoy gate is one such example, west of the main gate. Whereas the main gate is used for everyday passage, the imperial envoy gate is normally closed and used only for imperial visits.

more

03

天界橋Tenkaikyo

This is a bridge over the Houjou Ike pond. The name “Tenkai” refers to the fact that it served as a dividing line between the temple and the Imperial Palace. The Tenbun Rebellion of Tenbun 20 (1551), in which Shokoku-ji burned down, began on this bridge. It is still made of its original materials.

04

三門礎石Sanmonsoseki

Though several cornerstones are still left in the ruins of Sanmon, it has not been rebuilt since the Great Fire of Tenmei 8 (1788).

05

玉龍院Gyokuryuin

Gyokuryu-in was founded by the fifth high priest of Shokoku-ji, Unkei. Unkei was the disciple of the fourth high priest, Taisei, and they were both of the lineage of the Zen teacher Sesson Yubai. In order to invite Sesson Yubai’s heir, Taisei So’i (Shokoku-ji’s fourth chief priest) to Shokoku-ji, Ashikaga Yoshimitsu built it as a meditation space for him.

more

06

光源院Kogenin

Kogen-in, the pagoda of the 28th high priest Gen’yo of Shokoku-ji, was built in Oei 24 (1421) and known as Kotoku-ken. The head monk received dharma transmission from Master Fumyou the second, and he joined the temple on the 12th day of the eighth month of the same year. He passed away on the 27th day of the third month in Oei 32 (1425). In Eiroku 8 (1565), Ashikaga Yoshiteru passed away, and the Kotoku-ken — being his family temple — was renamed to Kogen-in in his honor.

more

07

林光院Rinkoin

Rinko-in was established after the early death of Ashikaga Yoshitsugu (also known formally as Rinko), second child of the third Ashikaga shogun Yoshimitsu and younger brother of the fourth Ashikaga shogun Yoshimochi, at the age of 25 in the first month of Oei 25 (1418). The temple was founded to pray for his happiness in the next world, and a shrine dedicated to Muso Soseki was transferred here. It was built on the former residence of the poet Ki Tsurayuki in Kyoto’s Nijo Nishi-no-Kyo.

more

08

普廣院Fukoin

Originally known as Kentoku-in. Seishin Enchi (also known as Kanchu), ninth head priest of Shokoku-ji, who received dharma transmission from Muso Soseki, received this building as a place of practice following Ashikaga Yoshimitsu’s profound conversion and withdrawal to religious life. In Kakitsu 1 (1441), the sixth Ashikaga shogun, Yoshinori, passed away and was given the name Fuko. His mortuary tablet was kept in this hall, and so in his honor, it was named Fuko-in.

more

09

養源院Yogenin

The founder of this hall was named Donchu Dobo. Since a young age, Master Juko (Kukoku Myo’o) visited to burn incense for the chief priest, Master Kukoku, and also participated as a student in a Zen retreat. He eventually received his dharma transmission, though he had little interest in practice outside of seated meditation, and thus wore the black robes for his whole life. He was particularly skilled in literary arts, and was well-liked by Ashikaga Yoshimitsu his son Yoshimochi. Eventually, they provided the Yogen-ken for Shokoku-ji’s Jotoku-in, and their abdication to the priesthood marked the beginning of Yogen-in.

more

10

仏殿跡Butsudenato

This hall has not been rebuilt since it burned down in the Ishibashi Rebellion in Tenbun 20 (1551). Presently, only the cornerstone remains.

11

大通院Daitsuin

Daitsu-in was built in the original town of Fushimi, on the grounds of Daikomyo-ji (presently the Shokoku-ji pagoda), as a temple for the originator of the Fushimi family, Prince Fushimi-no-Miya Yoshihito. In Oei 23 (1416), after Prince Yoshihito’s death, the hall was built on the Daikomyo-ji grounds and named Daitsu-in after his posthumous title of Daitsu. The founder of this hall was Muso Soseki.

more

12

弁天社Bentensya

The Founder’s Hall is located in the southwest. On the southern side, there is a small shrine with Kasuga-zukuri style pantile shingling, where a Benzaiten (Skt. Sarasvati) is enshrined.

more

13

洪音楼Koonro

This belfry has received the nickname “Ko’onro,” meaning ‘Tower of Flooding Sound.’ The original belfry burned down in the Great Tenmei fire. In the fourth month of Kansei 1 (1789), a bell was bought and placed in a temporary belfry, leading to the construction of the current building in Tenpo 14 (1843). It is also known as the ‘Hakama-wearing belfry,’ and is currently well-known for its grand size.

more

14

宗旦稲荷社Sotaninariyashiro

The god Sotan Inari is enshrined north of the belfry. It is said that the fox spirit known as Sotan-Gitsune appeared here. Around the beginning of the Edo period, a white fox lived on the Shokoku-ji grounds. This fox would occasionally transform into the appearance of a master tea ceremonialist, Sen Sotan (1578-1658). The fox would mingle and meditate with itinerant priests, sometimes playing Go with the temple’s master.

more

15

瑞春院Zuisyunin

On the northern side of the old imperial palace in Kyoto, within Shokoku-ji, is a hall known as Zuishun-in, which originated as the Uncho-in, created by Ashikaga Yoshimitsu as a hall for Sesson Yubai’s successor, Taisei So’i (who would become the fourth chief priest of Shokoku-ji), to meditate in when he came to the temple. Uncho-in later burned down during a war and was combined with Zuishun-ken. Zuishun-ken was built by authority of the monk Kisen Shusho, compiler of Inryo-ken’s records, during the Bunmei era (1484). Three years later, it burned down at the outset of the Tenmei era.

more

16

経蔵Kyozo

The kyozo, or the sutra repository, was built in Man’en 1 (1860) on the former site of a two-storied pagoda that had burned down in the Great Tenmei Fire. The kyozo was contributed by 120th head priest Master Eichu, who, when given the opportunity to restore the building, decided to give it an additional functionality as a repository.

more

17

後水尾帝髪歯塚Gomizunooteihatsushizuka

In Sho’o 2 (1653), Emperor Go-Mizunoo rebuilt a large tower that had burned down and put the hair and teeth from his tonsure inside one of the primary pillars. However, in Tenmei 8 (1788), during the Great Tenmei Fire, the building burned. Thus, this site is known as Hatsushitsuka, or “Hair and Teeth Mound.”

18

法堂Hatto

The lecture hall, with contributions made in Keicho 10 (1605) by Toyotomi Hideyori, has been rebuilt five times, and is the oldest Buddhist lecture hall in Japan. 28.72 meters in the front and 22.80 meters on the side, it is a truly grand building.

more

19

鎮守Chinju

At the time of its founding, the temple was located on the north of Imadegawa street, and it is said that the current Goshohachiman ward is built on its ruins. When Yoshimitsu welcomed the goshintai (object of worship) from Otokoyama Hachiman, the road from Otokoyama Hachiman to the temple was entirely covered in a white cloth.

20

天響楼Tenkyouro

Tenkyōrō (Heaven’s Sound Tower) is a new bell tower constructed in the summer of Heisei 22 (2011) for the celebration ceremony for the completion of the temple’s reconstruction. The bell is on of a set of two cast by China’s Daxiangguo Temple, one of which was contributed to this temple as a memorial of the flourishing of the Buddha’s Law in Japan and China and friendship between the two temples. They are engraved with the phrase “Friendship Memorial Bell” and the text of the Heart Sutra.

21

浴室Yokushitsu

The bathing quarters of Shōkokuji Temple are called “Senmyō” (“Clear Declaration”) and are believed to have been built around the year 1400. The current facilities were rebuilt in the first year of the Keichō era (1596), and then restored to their original condition in June of Heisei 14 (2002). The bathing quarters take their name from a drawing of a bath called “Tendōzan Senmyōsama” (“Senmyō of Tiantong Temple”) from a collection of drawings Zen buildings drawn in the Song era called “Taitōgzanshodōzu” (“Illustrations of the Temples of the Five Tang Mountains”).

more

22

方丈Hojo

A distinctive feature of Zen temple complexes is that the main gate, temple, lecture hall, and abbot’s chambers are constructed along a single axis from south to north. Shōkokuji Temple is no exception, with the abbot’s chambers built on the north side of the lecture hall. The abbot’s chambers of Shōkokuji Temple have been burned down several times since their original construction. The current building was rebuilt following the Great Tenmei Fire in the 4th year of the Bunka Era (1807), together with the main gate hall and temple kitchen. Its structure combines a hip-and-gable roof, tiled roof, and gable. With a crossbeam length of 25m and a beam length of 16m, it is a large scale structure for an abbot’s chambers. As such, in Heisei 19 (2007), it was designated a Tangible Cultural Property by Kyoto Prefecture.

more

23

大光明寺Daikomyoji

Daikōmyōji Temple was constructed before Shōkokuji Temple. In the second year of the Ryakuō era (1339), Kōgimonin Saionji Yasuko, the wife of the Emperor Gofushimite (1288-1336), began constructing a temple nearby the Fushimi Imperial Villa to mourn the death of her husband. The temple was named Daikōmyōji Temple, after the empress’s posthumous Buddhist name.

more

24

長得院Chotokuin

The meditation room and sub temple of Shōkokuji’s 19th abbot, Busui Seizoku Kokushi Gakuin Osho, are present and were originally called “Daidōin.” He continued the work and lineage of Chūshin Zekkai. In the Shitoku period (1384-87), he traveled through the Min Kingdom, participating in the history of several famous mountain dwellings for 10 years. Upon his return, he succeeded to the Zekkai Dharma lineage and spent time at Tōjiin Temple. In the 17th year of the Ōei era (1410), he joined Shōkokuji (19th abbot)

more

25

庫裏 「香積院」Kuri Kojakuin

The Zen temple’s kitchen has many gables. The entrance is on the gabled side. Its large gables and walls are particularly striking.

more

27

豊光寺Hokoji

After the death of Hideyoshi Toyotomi in August of the third year of the Keichō era (1598), the 92nd abbot of Shōkokuji, Oshō Saishō Shōtai, constructed Hōkōji Temple for Toyotomi’s death anniversary services.

He joined Shōkokuji on February 19th of the 20th year of the Tenshō era (1584). In July of the 20th year of the Keichō era (1607), Ieyasu Tokugawa visited Hōkōji, but Oshō Saishō passed away on December 27th of that year. After this, Hōkōji was destined to fall into disrepair before being burned in the Great Tenmei Fire of the eighth year of the Tenmei Era (1788).

more

28

開山堂庭園Kaizandoteien

As the name Founder’s hall suggests, it enshrines a wooden image of temple founder Teacher of the Nation Musō. It is to the east of the lecture hall and the most precious location on the grounds. In the first year of the Ōnin era (1467), it was burned by soldiers during the Ōnin War. In the sixth year of the Kanbun era (1666), Emperor Gomizunō reconstructed it for Imperial prince of Katsura No Miya and third generation Imperial prince Yasuhito, but in the eighth year of the Tenmei era (1788), it was once again burned down in the Great Tenmei Fire. In the last years of the Edo period, Monin Kyōrai, wife of Emperor Momozono, donated the grounds of the Kurogoden (the Black Palace) and the building was relocated there in the fourth year of the Bunka era (1807).

more

29

眞如寺Shinnyoji

In the Kamakura period, as the elder nun of Keiaiji Temple (one of the Five Mountain Nunneries of Kyoto) Muchaku Nyodai Oshō was nearing the end of her life, she created a cemetery at the foot of Mt. Kinugasa to enshrine the remains of her Dharma teacher and founder of Kamakura’s Engakuji Temple, Bukkō Kokushi (Zen Master Sogen Mugaku). The cemetery was named Shōmyakuan, and she protected it until the end of her life.

more

30

慈照院Jishoin

Around the 12th year of the Ōei era (1405), the resident Zen master (13th abbot of the Shōkokuji Head Temple) began constructing a temple complex called “Daitokuin.” In the end year of the Entoku era (1490) it became the resting place of Yoshimasa Ashikaga and was renamed “Jishōin” by imperial decree.

more

31

慈雲院Jiunin

Built in the Chōroku era (1457-59), the main object of worship is Shakyamuni Buddha.

The founder was the 42nd abbot of Shōkokuji Temple, Zen master Kōshūmeikyō Chokushi (Oshō Zuikeishūhō). The master was also a great scholar of Confucianism and prolific author who combined reverence for the emperor with faith in the shogunate.

more

32

法然水Hounensui

Before the establishment of Shōkokuji Temple, Pure Land school founder Hōnen Shōnin (St. Hōnen) revered the god Kamo Myōjin while living at Jingūji Temple on the Kudokuin Temple complex. Due to this, he made a pilgrimage to Kamo Shrine. Seeing the beautiful, clear waters of the garden lake of this combined shrine and temple, Hōnen Shōnin composed a song for himself about that complete clarity.

Shōkokuji Temple was later constructed on the remains of that combined shrine and temple. The lake is now a well known as the place where Shōnin drew the “Akasui” (“Waters of the Buddha”). There is a memorial monument and the town to the north gate is known as “Hōnensui” (“Waters of Hōnen”).

more

勅使門Chokushimon

There are many Zen temples with main gates in front and another gate alongside it. This imperial envoy gate is one such example, west of the main gate. Whereas the main gate is used for everyday passage, the imperial envoy gate is normally closed and used only for imperial visits. Another special element of the gate is that behind it (on the north side), a bridge extends in a slightly crank-shaped path over the Houjou Ike pond. It is thought to have been untouched in the Great Tenmei Fire and rebuilt around the Keicho era (1596-1615). On September 21st, 2004, a celebration was held for the completion of restorations, and in September 2007, it was designated a Tangible Cultural Property by the Kyoto prefectural government.

玉龍院Gyokuryuin

Gyokuryu-in was founded by the fifth high priest of Shokoku-ji, Unkei. Unkei was the disciple of the fourth high priest, Taisei, and they were both of the lineage of the Zen teacher Sesson Yubai. In order to invite Sesson Yubai’s heir, Taisei So’i (Shokoku-ji’s fourth chief priest) to Shokoku-ji, Ashikaga Yoshimitsu built it as a meditation space for him.

Afterward, towards the end of the era, Master Tenshin, successor to Master Hakuin-ka Torei, made significant contributions to the temple. Following this, during the Great Tenmei Fire in the fourth month of Tenmei 8 (1788), Tenshin was acting as the steward of the temple. As the flames encroached the corridor connecting the Founder’s Hall and the lecture hall, monks from Tofuku-ji and Rokuon-ji helped Tenshin in destroying the corridor and breaking out. It is because of this that the lecture hall remains today just as it did then. Afterward, Tenshin focused his efforts on restoration and took great pains to gather funds to rebuild the temple.

After the Meiji Restoration, the temple often lacked a head priest and was on the verge of collapse, until it was revitalized by the 13th high priest Ryokoku Ejo. In 1930, it was moved to its present location, keeping in large part its original appearance.

光源院Kogenin

Kogen-in, the pagoda of the 28th high priest Gen’yo of Shokoku-ji, was built in Oei 24 (1421) and known as Kotoku-ken. The head monk received dharma transmission from Master Fumyou the second, and he joined the temple on the 12th day of the eighth month of the same year. He passed away on the 27th day of the third month in Oei 32 (1425). In Eiroku 8 (1565), Ashikaga Yoshiteru passed away, and the Kotoku-ken — being his family temple — was renamed to Kogen-in in his honor. The original Kougen-in was located to the east of the present day temple, and while it was unaffected by the Great Tenmei Fire, it was destroyed in 1885. It merged with Zenno-in in 1896 and later separated from Zenno-in, becoming Kogen-in once more.

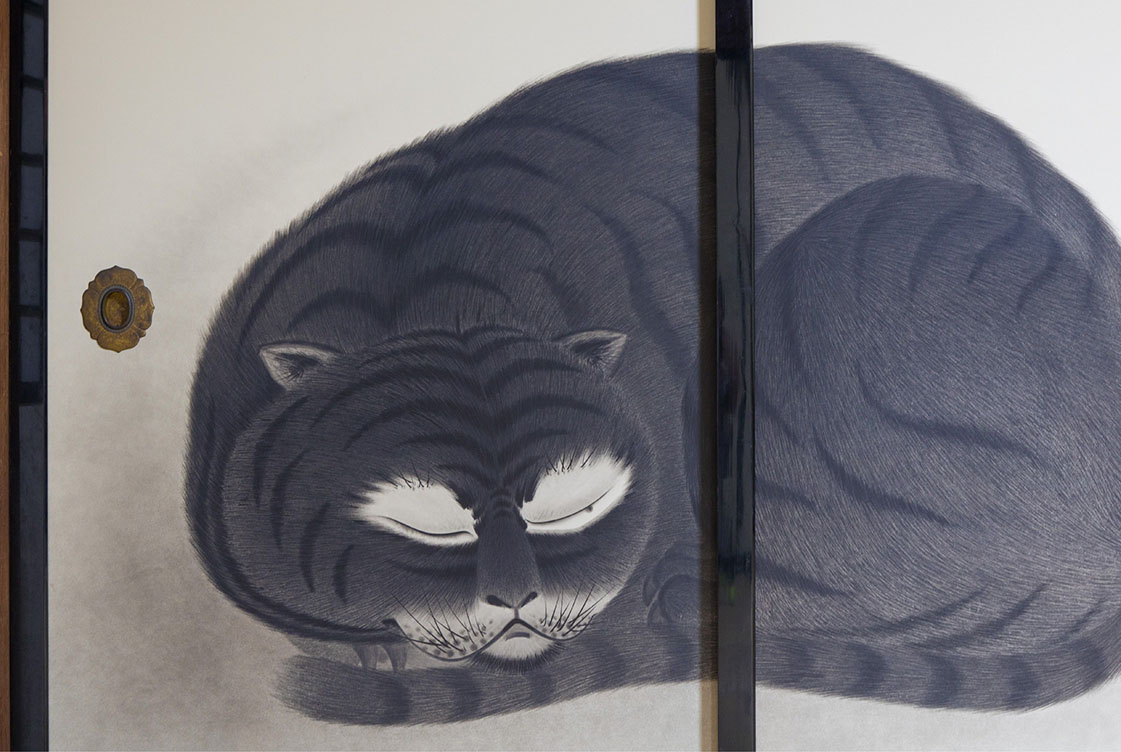

Incidentally, in the seventh month of Rokujo 9 (1604), Ikeda Terumasa of Bizen Province buried his late mother Zenno, having the temple built as a place to burn incense for her. In 1988, the main building and the head priest’s quarters were restored, and the redecorated main building’s altar room now holds a unique set of 12 sliding screens depicting the Chinese zodiac, planned and painted for half a year by a master painter selected by the JFAE, Mizuta Keisen.

林光院Rinkoin

Rinko-in was established after the early death of Ashikaga Yoshitsugu (also known formally as Rinko), second child of the third Ashikaga shogun Yoshimitsu and younger brother of the fourth Ashikaga shogun Yoshimochi, at the age of 25 in the first month of Oei 25 (1418). The temple was founded to pray for his happiness in the next world, and a shrine dedicated to Muso Soseki was transferred here. It was built on the former residence of the poet Ki Tsurayuki in Kyoto’s Nijo Nishi-no-Kyo.

After the Onin War, Rinko-in was moved to the side of Toji-in, and after that, it was transferred a number of times again; however, due to the frequently rotating chief priests, the exact details are unclear. Around the Genki Era (1570-72), while high priest Unshuku Shuetsu was in charge of the temple, he helped Toyotomi Hideyoshi in his expeditions to the Ming Dynasty and Korea. Hideyoshi rewarded him by giving Rinko-in its own land, which is located on the mountain of Shokoku-ji. Thus, Master Unshuku was the founding figure in Rinko-in’s revival.

In Keicho 5 (1600), during the Battle of Sekigahara, Shimazu Yoshihiro broke through both warring factions and hid in Iga Province. A wealthy Osakan merchant with whom Shimazu had been long-time friends, Tanabeya Imai Doyo, rushed to his hideout, giving him a ride on a ship from Sakai Harbor and escorting him safely back to Satsuma.

As appreciation for his outstanding actions, Shimazu relayed to him secret Satsuma medicinal arts. (This is the origin of Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharmaceuticals.) Later, when Doyo grew old and became unable to meet Yoshihiro in Satsuma, Yoshihiro had a statue of himself, built in the style of a Buddhist monk, and sent it to Doyo. Doyo had the Shorei-in temple built within Sumiyoshi Shrine, where that statue is now kept. After Yoshihiro’s death, his mortuary tablet was placed in the shrine, but when Shorei-in later fell into disrepair, Doyo’s descendant, Inuigake Bonjiku, became the fifth chief priest of Rinko-in and had Yoshihiro’s statue and mortuary tablet moved there. The Shimazu family then held a service for the transfer of the shrine. Because of this connection to the Satsuma domain, some Satsuma retainers still have graves in the Rinko-in graveyard today.

Tokugawa Ieyasu and his great Confucian teacher, Fujiwara Seika, are also interred there. In 1874, the temple, impoverished and in shambles, was finally abolished. It was revived in 1919 by the chief abbot of Shokoku-ji, Hashimoto Dokusan, who then became the head priest of the temple.

The current building is located in Nishi-ojimura, Hino-cho, Gamo-gun, Shiga Prefecture; the Nishoji domain owned by the Ichihashi clan in the Edo period and their residence (established in the Ansei era) have since been purchased and reconstructed elsewhere.

○ Oshukubai

A famous kind of plum tree known as the Oshukubai grows in this temple’s garden. According to the historical text, “The Great Mirror,” in the Tenryaku era (947-56) during the reign of Emperor Murakami, a plum tree in front of the imperial pavilion had withered. A tree from the estate of poet Ki Tsurayuki’s daughter was selected to replace it by force of imperial command.

However, affixed to the tree’s branch was a slip of paper with a poem written on it:

“The emperor commands it”

will not answer

the clever little

nightingale’s question

of his home

Upon reading the poem, the emperor was gripped with pity and compassion and decided to return the tree to its original location. This plum tree was then known as the Oshukubai, meaning “Nightingale’s Lodging Plum.”

Rinko-in was built in the remains of Ki Tsurayuki’s estate, and the Oshukubai prospered and decayed along with it in its garden. The temple had been relocated several times and then abolished over the course of a thousand years, and the Oshukubai had also been moved countless times. The chief priests of Shokoku-ji take pride in the effort put into assuring that this plum tree continues to bloom and that its impressive history is understood.

The nightingale changes

to his plum tree lodging

in the Spring.

How his heart must be

in the flowers!

(Shimazu Iehisa)

Not growing

in my home,

only the plum tree suits.

Perhaps if I think on the branches

of those renowned flowers

(Kishitani Goro)

Many such poems about the Oshukubai exist.

普廣院Fukoin

Originally known as Kentoku-in. Seishin Enchi (also known as Kanchu), ninth head priest of Shokoku-ji, who received dharma transmission from Muso Soseki, received this building as a place of practice following Ashikaga Yoshimitsu’s profound conversion and withdrawal to religious life. In Kakitsu 1 (1441), the sixth Ashikaga shogun, Yoshinori, passed away and was given the name Fuko. His mortuary tablet was kept in this hall, and so in his honor, it was named Fuko-in.

The third head priest of the temple, Chuho Chusei (also known as Chusei Soshu) wrote characters upon coins used during the time of the Yongle Emperor Zhu Di. Following the disasters of the Onin War and during the tenure of the fourth head priest, Bunrin Eishu (also known as Keishu), new plans were made to divide the borders of the area (the illustration of which remains in this temple), and around Eisho 7 (1510), the Reizei family contributed part of their former estate that had been joined with Fujiwara no Teika’s graveyard to the temple. In other words, they entrusted the grave to the temple and in return gave land proportionate to the cost of an ancestral hall, greatly increasing the size of the temple grounds. The eighth head priest, Seishuku Jusen, was born to the Reizei family, demonstrating just how close the family was with Fuko-in.

Reconstruction after the Great Tenmei Fire was slow but finally finished in the fifth month of Kaei 1 (1848). In 1920, the hall was relocated to the former site of Rokuon-in, where it remains today.

養源院Yogenin

The founder of this hall was named Donchu Dobo. Since a young age, Master Juko (Kukoku Myo’o) visited to burn incense for the chief priest, Master Kukoku, and also participated as a student in a Zen retreat. He eventually received his dharma transmission, though he had little interest in practice outside of seated meditation, and thus wore the black robes for his whole life. He was particularly skilled in literary arts, and was well-liked by Ashikaga Yoshimitsu his son Yoshimochi. Eventually, they provided the Yogen-ken for Shokoku-ji’s Jotoku-in, and their abdication to the priesthood marked the beginning of Yogen-in. In Oei 16 (1409), Juko passed away at the age of 43. He was honored with a million prayers at Chosei-ken on Mt. Higashiyama. Chosei-ken was later changed to Chinzo-ken, and as more came to retire in Jotoku-in, it was renamed Yogen-in. On the 33rd anniversary of Donchu Dobo’s death, the 79th head priest of Shokoku-ji, Osen Keisan, burned incense at Yogen-in and became the former’s successor. He then relocated Yogen-in to Shokoku-ji and became its second head priest. In Koka 2 (1845), the hall was moved to its current location. Yakushi Nyorai (Skt. Bhaisajyaguru) is the principal image of this hall, and a Bishamonten (Vaishravana) was also enshrined in the Kamakura period, attracting local devotion.

大通院Daitsuin

Daitsu-in was built in the original town of Fushimi, on the grounds of Daikomyo-ji (presently the Shokoku-ji pagoda), as a temple for the originator of the Fushimi family, Prince Fushimi-no-Miya Yoshihito. In Oei 23 (1416), after Prince Yoshihito’s death, the hall was built on the Daikomyo-ji grounds and named Daitsu-in after his posthumous title of Daitsu. The founder of this hall was Muso Soseki.

Daikomyo-ji was renovated in the early 1600s and moved inside of Shokoku-ji. Daitsu-in also became part of Shokoku-ji at the same time.

In An’ei 2 (1773), Master Seisetsu Shucho (also known as Master Daiyo) took charge of renovations and opened the meditation hall. In Bunka 1 (1804), he moved the hall to its present location and completed the construction of the current seated meditation hall.

In Kaei 4 (1851), Master Daisetsu Shoen built the current main building and head priest’s quarters. giving Daitsu-in and the meditation hall large roles in the temple. In the first year of the Meiji era (1868), the hall was combined with Daichi-in, where it now remains.

This hall has also served as a specialized training facility for ascetic practices. The seated meditation hall is a large, square room, where ascetic monks gather day and night for mendicancy and meditation.

弁天社Bentensya

The Founder’s Hall is located in the southwest. On the southern side, there is a small shrine with Kasuga-zukuri style pantile shingling, where a Benzaiten (Skt. Sarasvati) is enshrined.

This Benzaiten had been enshrined in Kuni-no-Miya Imperial Garden estate as the family’s guardian deity since ancient times, but in 1880, the family moved to Tokyo, and the 126th head priest of Shokoku-ji, Ogino Dokuon, received the image from second-rank Prince Asahiko. Ogino then enshrined the Benzaiten, attracting many local worshippers. In 1957, this story prompted the revival of a Benzaiten-related lecture group, though this is no longer active.

Examination of the current building suggests that it was originally built in the latter half of the 17th century. This shrine is not included in an 1871 map of the temple grounds. Since a Meiji-era engraving can be found on the foundation, it is likely because it was originally in a different location and relocated to its current spot.

This shrine was designated a Tangible Cultural Property by the Kyoto prefectural government in 2007.

洪音楼Koonro

This belfry has received the nickname “Ko’onro,” meaning ‘Tower of Flooding Sound.’ The original belfry burned down in the Great Tenmei fire. In the fourth month of Kansei 1 (1789), a bell was bought and placed in a temporary belfry, leading to the construction of the current building in Tenpo 14 (1843). It is also known as the ‘Hakama-wearing belfry,’ and is currently well-known for its grand size. A Bonsho bell is suspended above the belfry, with each of its sections carrying many inscriptions. These inscriptions express wishes for favorable climates, lack of disasters and wars, and peace and prosperity for the land’s people. Next to them, an inscription indicates the date of its construction in 1629. This structure was designated a Tangible Cultural Property by the Kyoto prefectural government in 2007.

宗旦稲荷社Sotaninariyashiro

The god Sotan Inari is enshrined north of the belfry. It is said that the fox spirit known as Sotan-Gitsune appeared here.

Around the beginning of the Edo period, a white fox lived on the Shokoku-ji grounds. This fox would occasionally transform into the appearance of a master tea ceremonialist, Sen Sotan (1578-1658). The fox would mingle and meditate with itinerant priests, sometimes playing Go with the temple’s master.

Sometimes, when the fox was done imitating Sotan, he would head to a local tea ceremonalist’s house, drinking tea and eating sweets while ravaging the place. Other times, however, the Sotan-Gitsune would hold tea ceremonies at the Jisho-in pagoda. His etiquette at these ceremonies was shockingly refined, so much so that when Sotan himself would eventually arrive, he was quite impressed. And there is yet another story about this fox taking the form of Sotan.

This story is called “The Ishinshitsu,” and is still told today at Jisho-in. In the story, after the Sotan-Gitsune rampages in the tea house and breaks its window, the window is repaired but ends up much larger than a normal tea house window.

It is also said that on one occasion, after the Sotan-Gitsune stole some fried tofu from a store, he fell down a well while being chased and died. In some versions of this story, he was shot by a hunter. The monks mourned the death of this fox, who was not even transformed at the time and who had often brought joy to people by teaching them Zen, and so they built him a small memorial shrine. This memorial remains as the Sotan Inari shrine.

The first appearance of this story in literature was in 1830 in “Tea House Rumors” (Kissa Yoroku), written by Fukada Kojitsu, a renowned Confucian scholar from Owari.

瑞春院Zuisyunin

Zuishun-in: The Floating Elegance of the Suikinkitsu and “Temple of the Wild Geese”

On the northern side of the old imperial palace in Kyoto, within Shokoku-ji, is a hall known as Zuishun-in, which originated as the Uncho-in, created by Ashikaga Yoshimitsu as a hall for Sesson Yubai’s successor, Taisei So’i (who would become the fourth chief priest of Shokoku-ji), to meditate in when he came to the temple. Uncho-in later burned down during a war and was combined with Zuishun-ken. Zuishun-ken was built by authority of the monk Kisen Shusho, compiler of Inryo-ken’s records, during the Bunmei era (1484). Three years later, it burned down at the outset of the Tenmei era. It was rebuilt between the Koka era and the Kaei era (1845-1849). After this, although all the buildings were abandoned, they were successfully revived in June 1898 and now exist as the modern Zuishun-in. Incidentally, many artists and writers — such as Kisen Shusho, Suzuki Shonen, and Mizukami Tsutomu — have been inspired by and have connections to Zuishun-in.

Principal Image

Amida Triad (Wooden cloud-top raigo, from the Fujiwara era)

The principal image of Zuishun-in was donated on the 13th day of the 4th month of Eikyo 11 (1439) by the sixth Ashikaga shogun, Yoshinori. As detailed in the Inryo-ken records, the principal image is a triadic statue, the center of which is Amida Nyorai (Skt. Amitabha Tathagata), forming the raigo mudra and seated in the lotus position. Also riding clouds in raigo position are Kannon Bosatsu (Skt. Avalokiteshvara Bodhisattva) offering a lotus and Seishi Bosatsu (Skt. Mahasthamprapta Bodhisattva) with his hands pressed together in prayer.

The central figure of this wooden triad has crystals inlaid for his urna and hair jewel, and both of the flanking images have metal diadems and necklaces separately affixed. The details of the image’s construction are unknown.

The central statue’s mild countenance that resembles the master sculptor Jocho, the fine coils of its hair, and the fluid lines on the garments all mark it as being from the middle of the Fujiwara period.

The flanking images were likely made in a later period. It could also be that a disaster, such as a fire, destroyed all but the central image, and so the flanking images had to be replaced.

The aureolas and pedestals are elegantly and elaborately crafted, likely made around the beginning of the Edo period. It is quite possible that whenever a serious disaster occurred, only the body of the statue was saved, and what remain today are therefore the more recent and sophisticated ornamentations of the early Edo.

| Measurements |

| Amida Nyorai (Skt. Amitabha Tathagata) |

Height |

35.2 cm |

Height w/o Hair |

32.8 cm |

|

| Kannon Bosatsu |

Height |

20.1 cm |

|

|

|

| Seishi Bosatsu |

Height |

20.6 cm |

|

|

|

| 68 cm from bottom of pedestal to tip of aureola |

Appraisal by Kuno Ken (Cultural Heritage Committee Member)

Painted Fusuma

| Peafowl |

Imao Keinen |

|

|

|

|

| Old pine |

Suzuki Shonen |

|

|

|

|

| Watchful dragon |

Umemura Keizan |

|

|

|

|

| Wild geese |

Ueda Manshu |

|

|

|

|

Hanging scroll

| Tao Yuanming |

Spring and Autumn landscape |

|

Set of three |

Kano Tan’yu |

|

| Zhong Kui |

Peony |

Tiger in bamboo |

Set of three |

Kano Yasunobu |

Changing of the four seasons |

| Fukurokuju |

Plum blossom in snow |

Plum blossom and moon |

Set of three |

Imyo Shokei |

|

| Red-clothed Daruma |

|

|

|

Kano Tsunenobu |

|

Minakami Tsutomu and the Temple of Wild Geese

When Naoki Prize-winning author Minakami Tsutomu was nine years old, he became a monk at Zuishun-in and practiced Zen until he was 13 before suddenly leaving the temple. Afterward, he traveled across the country and devoted himself to writing. In 1961, he published his best-selling novel, Temple of the Wild Geese, based on his recollections of painted fusuma panels at Zuishun-in, giving the hall the nickname “Temple of the Wild Geese.” Even now there remains a space in the upper portion of the main building, known as the Wild Geese Alcove, that contains eight fusuma painted with wild geese.

The Garden

South Side: Uncho (Cloud Top) Garden

This rock garden exemplifies Muromachi-period style with an elegant simplicity and a koan theme representative of the Zen worldview.

North Side: Unsen (Cloud Spring) Garden

Muraoka Tadashi (horticultural authority for the Cultural Achievement Award and special member of the Cultural Preservation Board) created this pond garden in the style of Shokoku-ji’s founder, Master Muso Soseki.

Tea Room The Kyusho-an

The Kyusho-an is a sukiya-style tea room built by master craftsman Morotomi Atsushi and modeled after Fushin-an of the tea house Omotesenke. The nameplate was written by Sen Sosa (also known as Jimyosai).

The Study Unsen-ken

The main material for the Unsen-ken was a thousand-year-old Taiwanese cypress two meters in diameter. The ceiling is elegantly detailed, resembling a game of Go. Additionally, looking out from the study’s bell-shaped window, one finds a picturesque scene of a yunoki-style stone lantern amid a grove of cypress. Furthermore, the room contains fusuma panels painted with images of old pines, an excellent work by Suzuki Shonen during his stay at Zuishun-in.

The Suikinkitsu

Zuishun-in’s garden holds a suikinkitsu, a set of bamboo pipes that create music when water flows through them, made 370 years ago in the style of the one found in the garden of artist Kobori Enshu’s Fushimi estate, whose ethereal tones have brought the hearts of many listeners to a world of mysterious beauty.

The Big Tea Bowl

This tea bowl was made by potter Kato Kazuhiro (recipient of the Tomimoto Kenkichi Prize, the Kyoto Excellence in Fine Arts Prize, and more); inspired by the sounds of the haunting earthen tones of suikinkitsu outside the Kyusho-an tea house, it was named “Suikin.” Suikin is 49 centimeters in diameter and weighs 7 kilograms. It is Japan’s finest Irabo-glazed teacup, and is still held in the spot for primary tea bowls in Zuishun-in.

経蔵Kyozo

The kyozo, or the sutra repository, was built in Man’en 1 (1860) on the former site of a two-storied pagoda that had burned down in the Great Tenmei Fire. The kyozo was contributed by 120th head priest Master Eichu, who, when given the opportunity to restore the building, decided to give it an additional functionality as a repository. However, as the Buddha’s ashes that were once held in the building have been moved to a separate hall, the building now serves only as a kyozo, holding the complete Goryeo scriptural collection (though the Mahaprajnaparamita sutra is the Puning edition from the Yuan dynasty). This shrine was designated a Tangible Cultural Property by the Kyoto prefectural government in 2007.

法堂Hatto

Lecture Hall

![Lecture Hall]()

The lecture hall, with contributions made in Keicho 10 (1605) by Toyotomi Hideyori, has been rebuilt five times, and is the oldest Buddhist lecture hall in Japan. 28.72 meters in the front and 22.80 meters on the side, it is a truly grand building.

Commentary

The lecture hall, also known as Muido, or the No-Fear Hall, is intended as a place to fearlessly expound the dharma and to give lectures advocating the revival of all sentient beings to live free from the suffering incurred by worldly desire. After a period when this temple lacked a proper shrine, the principal image was enshrined here, giving this building a double-function as the main hall.

When it was originally built in 1391, the building was known as the Horaido, or the “Dharma Thunder Hall.” Afterward, it burned down four times, and then once more in Tenbun 20 (1551) during a battle. Afterward, it was rebuilt in Keicho 10 (1605) under the authority of Tokugawa Ieyasu, with the use of 15,000 stones donated by Toyotomi Hideyori. Thus, the building is currently in its fifth iteration.

Being the oldest Buddhist lecture hall in the country, it was designated a Special Protection Building in 1910, an Old National Treasure in 1929, and an Important Cultural Property in 1950 by the Cultural Preservation Act.

The irregular stone foundation serves to amplify the hall’s composed, elegant, and dignified image. It stands 22 meters high.

It has seven beams, six joists, one floor, and a single-layered hip-and-gabled roof, creating a striking image of Zen architecture. The entrance hall also has an additional four beams, one joist, and a single-layered gabled roof.

Zen Architectural Features

In the early Kamakura period, Song Chinese architectural styles were imported to Japan alongside Zen Buddhism. Buildings were also made taller starting from this period.

Roofs

Zen roofs typically have eaves that curve at both ends.

Crosspieces

The crosspiece is a fundamental structure that connects and reinforces beams.

Rafters

The rafters are arranged radially under the eaves in a pattern resembling a folding fan.

Ceiling

The boards of the ceiling are arranged into a plain, flat surface resembling a mirror. This was particularly favored in Zen architecture after the Kamakura period.

Beams

The thin, cylindrical beams are supported by round granite bases. Similarly to Greek entasis, this gives the beams a greater sense of stability.

Kumimono (support brackets)

“Tsumegumi” are support brackets that press the support blocks together tightly. Support brackets are also arranged in the space between the pillars.

Tengai (reed cap) and Ban (flag)

The tengai was originally developed as a cap used for preaching the Buddha’s Law outdoors ( as an umbrella to protect from the sun or rain). Also, the hatahoko and ban are flags raised as symbols. The hatahoko are also called “hanging banners,” while the ban are also called “flags.” Banners, flags, and hoods are all solemnly used before the Buddha, and are called “bangai” (“banner and cap”). The Buddha’s religious law is often compared to a banner, and preaching the law is thus sometimes called “raising the banner of the law.”

Shumidan (the altar enshrining Shinran’s portrait)

![Shumidan (the altar enshrining Shinran's portrait)]()

When entering the lecture hall, at the front is a tall altar with stairs on three sides. This is the Shumidan. In the center of the Shumidan is the main object of worship, Shaka Nyorai (Shakyamuni Buddha). Enshrined beneath his left arm is an image of Anan Sonja (St. Ānanda) and beneath his right arm is Kashō Sonja (St. Mahākāśyapa)

On the ceiling is the Banryūzu (coiled dragon image), which is famous under the name “nakiryū” (“roaring dragon”).

Additionally, images of masters Daruma (Bodhidharma), Rinzai, Hakujō, and temple founder Teacher of the Nation Musō are enshrined on the western altar. On the eastern altar are Daigen Shuri Bodhisattva and Yoshimitsu Ashikaga.

Main object of worship Shaka Nyorai (Shakyamuni Buddha)

![Main object of worship Shaka Nyorai (Shakyamuni Buddha)]()

Height: 110 cm

The main image of the Buddha is usually enshrined in a Buddha hall, but after this temple’s Buddha hall was burned down during the Ōnin War (1467-1477) it was not rebuilt. Accordingly, the lecture hall has also functioned as a Buddha hall since Year 10 of the Keichō era (1605).

This image, as well as the images of Anan and Kashō beneath its arms, were sculpted in the Kamakura period (1185–1333). They are leading images of the period, said to have been crafted by the famed sculptor Unkei. Unkei, following in the path of his father Kōkei, was a Buddhist sculptor who perfected a vigorous realist style. Some of his main works are said to be the Dainichi Nyorai of Enjōji Temple, various Buddhas of Kōfukuji Temple’s Hokuendō, and the image of Niō at the Nandaimon Gate of Tōdaiji Temple, but this image is one of his most excellent works. Sitting on a massive bed of lotuses with legs crossed in full lotus position, this image of the form of meditative concentration is truly beautiful, giving the viewer a sense of great power.

Anan Sonja (St. Ānanda)

![Anan Sonja (St. Ānanda)]()

Wooden image of Anan Sonja (Anan Sonja Mokuzō)

Height: 126 cm

Anan was born from the Shakya clan of the ancient city of Kapilavastu and was a cousin of Sakyamuni. He was born with handsome features – a face like the pure full moon, eyes like blue lotuses, and a body like the pure light of a polished mirror. Of the ten principal disciples of the Buddha, he is said to have listened the most to the Buddha’s teachings. In India, learning is not usually done from books, but by oral transmission from master to disciple. For this reason, reading or learning are called “listening.” For this reason, if a person has “listened a lot,” it means that they have extensive and deep knowledge. Anan was certainly the most intellectual of the disciples.

Modern sutras are said to have been written from Anan’s memory.

Kashō Sonja (St. Mahākāśyapa)

![Kashō Sonja (St. Mahākāśyapa)]()

Wooden image of Mahākāśyapa Sonja

Height: 126 cm

“Mahākā” means “great.” Kashō Sonja is famous as one of the ten principal disciples of the Buddha, as well as for his practice of Zudagyō (abandoning desires and disciplining the body). His hands, firmly pressed together, show his indomitable heart of prayer and his firm will can be seen around his mouth. Furthermore, his wide open eyes splendidly express his leadership as the head of a religious organization.

Banryūzu (coiled dragon image)

![Banryūzu (coiled dragon image)]()

By Mitsunobu Kanō (Diameter: approximately 9m)

Zen lecture halls often have dragons painted on their ceilings. Dragons are mythical beasts said to protect the Buddha’s Law. Their leaders are called “Dragon Kings” or “Dragon Gods,” and are counted as one of the Eight Legions of Buddhist deities.

In the tenth year of the Keichō era (1605), when reconstruction of Shōkokuji Temple’s lecture hall was completed, this image painted by Mitsunobu Kanō was distinctly drawn as a full portrait within an Ensō (a circular symbol of enlightenment or the universe). Its colors remain quite beautiful to this day. Clouds were painted outside the Ensō, but due to peeling very little now remains. According to Einō Kanō (1631-97), who compiled the Honchōgashi (the most essential book in the study of Japanese art history), this painting was done by Mitsunobu Kanō (1565-1608) Though unsigned, it is undoubtedly the work of Mitsunobu.

Daruma (Bodhidharma)

![Daruma (Bodhidharma)]()

Wooden carving of Great Teacher Daruma (Bodhidharma)

The First Patriarch of Zen. Born to an Indian royal family, Shakyamuni Buddha is the 28th named Buddha. He crossed over into China in the first year of the second era of Emperor Wu of Liang (520). At Nanking, he had dialogues with Emperor Wu of Liang, then meditated facing the wall of a cave on the grounds of the Shaolin Monastery in Henan Province. Following this, he passed on the Buddhist Law to Huike, the Second Patriarch.

Zen masters Rinzai and Hyakujō

![Zen masters Rinzai and Hyakujō]()

(Left) Zen Master Gigen Rinzai

The 11th founder, counting from Great Teacher Daruma (Bodhidharma). The founder of the Rinzai School, his words and deeds are recorded in the “Rinzairoku” (“The Record of Rinzai”).

(Right) Zen Master Ekai Hyakujō

The 9th founder, counting from Great Teacher Daruma (Bodhidharma). He established the rules of Zen in the “Hyakujō Shingi.” He is famous for his words, “If you do not work for a day, you do not eat for a day.”

Temple founder, Musō Kokushi

![Temple founder, Musō Kokushi]()

Wooden image of Soseki Musō

Daigen Shuri Bodhisattva

![Daigen Shuri Bodhisattva]()

Wooden image of Daigen Shuri Bodhisattva (Daigen Shuri Bosatsu) Muromachi period

A Chinese guardian deity of Ocean Voyages, who protects the safety of those on boats. After being worshiped as the guardian deity of the various temples and monasteries at the Ayuwang Temple complex on Mt. Yuwangshan, he has been enshrined as guardian deity of temples and monasteries in Zen temples.

Yoshimitsu Ashikaga

![Yoshimitsu Ashikaga]()

Dressed in the full garments of Japanese court nobility, this is said to be an image of Yoshimitsu on the occasion of his inauguration as the emperor’s chief advisor at 34 years old.

About the disassembly and grand reconstruction

Due to severe damage to the lecture hall, in recent years a disassembly and grand reconstruction of the lecture hall took place. This was performed as a memorial of the 600th anniversary of Teacher of the Nation Fumyō’s death. Construction began on January 1st of Heisei 2 (1990). On February 2nd, Heisei 7 (1995) the ridgepole raising ceremony was performed, with completion of construction on March 31st, Heisei 9 (1997). In the reconstruction, half of the roof tiles were reshingled, the Shumidan carvings and ceiling mural were resin treated to prevent peeling, the Shumidan and memorial tablet altar lacquer was repaired, the floor coverings were replaced, and the wall plaster was repainted, among other things.

浴室Yokushitsu

The bathing quarters of Shōkokuji Temple are called “Senmyō” (“Clear Declaration”) and are believed to have been built around the year 1400. The current facilities were rebuilt in the first year of the Keichō era (1596), and then restored to their original condition in June of Heisei 14 (2002). The bathing quarters take their name from a drawing of a bath called “Tendōzan Senmyōsama” (“Senmyō of Tiantong Temple”) from a collection of drawings Zen buildings drawn in the Song era called “Taitōgzanshodōzu” (“Illustrations of the Temples of the Five Tang Mountains”). In the Suramgama Sutra, it is written that when the Sixteen Bodhisattva were holding a memorial service at a bath, the various Bodhisattvas (starting with Bhadrapāla Bodhisattva) realized that their selves were one with the water. At that time, Bhadrapāla Bodhisattva said, “Profoundly and clearly do I declare, a Buddha is here.” And so “Senmyō” means to make clear or plain. Due to this incident, bathing quarters in Zen temples are called “Senmyō” in honor of Bhadrapāla Bodhisattva. In Zen it is said that “Dignified Forms are Instant Dharma,” meaning that our daily movements and actions are a place for ascetic training. As such, although bathing quarters are one of the traditional building facilities in temple complexes, they more importantly fulfill a vital role in ascetic discipline by removing the dirt from both the mind and body. As the right to bestow the name “Senmyō” was limited to the Imperial Household and the Shogunate families, when the Shogun Yoshimitsu Ashikaga constructed Shōkokuji Temple, he gave in the name Senmyō as well. This shrine was designated a Tangible Cultural Property by the Kyoto prefectural government in 2007.

方丈Hojo

Abbot’s chambers

![Abbot's chambers]()

A distinctive feature of Zen temple complexes is that the main gate, temple, lecture hall, and abbot’s chambers are constructed along a single axis from south to north. Shōkokuji Temple is no exception, with the abbot’s chambers built on the north side of the lecture hall. The abbot’s chambers of Shōkokuji Temple have been burned down several times since their original construction. The current building was rebuilt following the Great Tenmei Fire in the 4th year of the Bunka Era (1807), together with the main gate hall and temple kitchen. Its structure combines a hip-and-gable roof, tiled roof, and gable. With a crossbeam length of 25m and a beam length of 16m, it is a large scale structure for an abbot’s chambers. As such, in Heisei 19 (2007), it was designated a Tangible Cultural Property by Kyoto Prefecture.

Etymology

The etymology of the Japanese word “hōjō” (abbot’s chambers) comes from the Vimalakirti Sutra, a 1st-2nd century Mahayana scripture. In it it is said that each side (hō) of the lay practitioner Vimalakīrti’s living space was only one jō long (about 1.8 meters). As such, “hōjō” has come to indicate the living quarters of the abbot. By extension, the abbot himself is also sometimes called “hōjō.” The framed calligraphy hanging over its gate is by the famed Chinese calligrapher Zhang Fuzhi, featuring a Japanese zelkova tree carved out of one piece.

Garden behind the abbot’s chambers

![Garden behind the abbot's chambers]()

While the front yard is a simple structure covered in white sand, its effect is not simply to properly express the form of the lecture hall. The white sand utilizes reflected sunlight to brighten the inner area.

There are six spaces, with three rooms on the north and three to the south. Though “six spaces” may sound small, these are not small rooms. Including the front abbot’s chambers and rear abbot’s chambers, the size is about 306m.

Inside the abbot’s chambers

![Inside the abbot's chambers]()

Chūgoku Fudarakusenzu (“Illustration of China’s Mt. Putuo”) By Zaichū Hara

All of the cedar door paintings around the abbot’s chambers are by Zaichū Hara.

He painted Mt. Putuo, which is considered the sacred grounds of Kannon Bodhisattva in China.

Bamboo room

![Bamboo room]()

Bamboo illustration By Gyokurin

Painted by the Pure Land monk Gyokurin, a friend of Oshō Imyō (the 115th abbot) while he was staying at the temple.

Plum room

![Plum room]()

Old plum tree illustration by the 115th abbot, Shūkei Imyō

This painting was not done by a professional painter, but by Shōkokuji Temple’s 115 abbot, Shūkei Imyō Oshō Imyō was born in Wakasa and was head abbot of Kogenin Temple in Yamauchi before becoming head abbot of this temple. He was skilled in painting from a young age. He learned painting under Itō Jakuchū from after becoming head abbot of Kogenin Temple. The famous works of Jakuchū’s that he studied closely are truly wonderful; works such as “Shakasanzonzō” (a painting of Buddha with two Bodhisattva) and “Dōshoku Saie” (“Colorful Realm of Living Beings”). His strokes in painting plums were in particular regarded the greatest in the land. He painted the abbot’s chambers’ twelve large sliding doors with a series of large old plum trees.

The imperial house gift room

![The imperial house gift room]()

Cherry trees of Mt. Yoshino By the Tosa School

A sliding door painting by a nobleman, received from the emperor’s pavilion in the Heian palace. It splendidly portrays the roundness of the mountains and the gentleness of the cherry trees and pines. The painter is said to be Tosa Mitsuoki, who revived the Tosa School at the beginning of the Edo era, but it is not known for certain.

Koto, go, calligraphy, and painting room

![Koto, go, calligraphy, and painting room]()

Koto, go, calligraphy, and painting illustration By Zaichū Hara

A painting on the theme of the etiquette of the Chinese literary elites in the four pursuits of playing the koto, playing go, writing calligraphy, and painting.

The abbot’s messenger room

![The abbot's messenger room]()

Illustration of the Eight Immortals By Zaichū Hara

Sliding door painter

Zaichū Hara

A work by the founder of the Hara School, signed under the pen name “Gayū.” Born in Kyoto in the 3rd year of the Kan’en era (1750). It is said that his teacher was Yūtei Ishida (1721-1786), who was active in the mid-Edo Kyoto art scene with the Kanō School. Above all skilled at paintings of animals and flowers in nature, none of the talent shown in his skilled paintings excels the one held in this temple. His colors were in particular very subtle. Died in the eighth year of the Tenpō era (1837). 88 years old at his death. Buried in the Hara family grave at the Tenshōji Temple of the Pure Land school. His posthumous Buddhist name is “Gayū Murō Dakeyo Zaichū Tōgen Koshi.”

The monk Gyokurin

A monk of Ōmi, his birth name was “Seisui” and also used the name “Bokusekidō.” The disciples of monk Gokurin lived at the Mt. Rakuto temple. He learned painting from his teacher and was skilled at black ink paintings of bamboo. He passed away in the 11th year of the Bunka era.

The abbot’s chambers gate

The entry gate to the front of the abbot’s chambers is a shikyakumon (a four-pillared, gabled gate about two metres across with a single door). The curved roof employs a karahafu (a type of cusped gable). This shrine was designated a Tangible Cultural Property by the Kyoto prefectural government in 2007.

大光明寺Daikomyoji

Daikōmyōji Temple was constructed before Shōkokuji Temple. In the second year of the Ryakuō era (1339), Kōgimonin Saionji Yasuko, the wife of the Emperor Gofushimite (1288-1336), began constructing a temple nearby the Fushimi Imperial Villa to mourn the death of her husband. The temple was named Daikōmyōji Temple, after the empress’s posthumous Buddhist name.

The empress, as the mother of Imperial Princess Kūko, Emperor Kōgon, Imperial Prince Keijin, and Emperor Kōmyō, was a great support to the Northern Court, but in the 12th year of the Shōhei era (1357), she passed away at age 65. She composed many poems that appear in collections of poetry such as the “Gyokuyōshū” and the “Shinsenzaishū.”

After the empress’ grandson, Imperial Prince Yoshihito of the Fushinomiya branch of the Imperial family, was buried and enshrined in the temple, it became the temple where the memorial tablets of the Fushinomiya family were interred. Afterwards, it experienced impoverishment and a fire in the middle of the Keichō era (1596-1615), but in the first year of Genna (1615), it was revitalized as a sub temple of Shōkokuji Temple by Ieyasu Tokugawa.

In the 36th year of the Meiji era (1903), Daikōmyōji Temple was once again destroyed in the Great Tenmei Fire that also burned down the sub temple Shingein and Shōkokuji Temple. It was merged with the three temples of Jōtokuin and then revived as a temple on the grounds of Shingein Temple with the name “Daikōmyōji.” A wooden image of the founder of Jōtokuin, the Zen master Myō-ō Kūkoku, is enshrined at this temple. It is also the sub temple of Yoshihisa (Jōtokuin Densō Daishōkoku Ippin Essan Michiji Daikoji), the 9th Shogun of the Ashikaga

Successive generations of abbots include Shōtai Saishō (92nd abbot of Shōkokuji), the Meiji era Zen scholar, Zen master Dokuon Ogino (126th abbot of Shōkokuji, 1st special resident), and Zen master Rekidō Ōtsu (130th abbot of Shōkokuji, fifth special resident) in the modern era.

長得院Chotokuin

The meditation room and sub temple of Shōkokuji’s 19th abbot, Busui Seizoku Kokushi Gakuin Osho, are present and were originally called “Daidōin.” He continued the work and lineage of Chūshin Zekkai. In the Shitoku period (1384-87), he traveled through the Min Kingdom, participating in the history of several famous mountain dwellings for 10 years. Upon his return, he succeeded to the Zekkai Dharma lineage and spent time at Tōjiin Temple. In the 17th year of the Ōei era (1410), he joined Shōkokuji (19th abbot)

He also opened Zuiunji Temple in Suō in response to a request from Yoshihiro Ōuchi. He then lived in Hōkanji Temple in Awa. In the 24th year of the Ōei era (1417), he joined Tenryūji Temple, retiring from active service on September 5th. After this he led a secluded life reviving Gyūkōji Temple in Tosa. He passed away at that temple on August 18th, 32nd year of the Ōei era (1425). On February 27th of the same year, Yoshikazu passed away, taking the posthumous name “Hisatokuindono.” That temple was made into a mausoleum and renamed “Hisatokuin Temple.” After the Great Tenmei Fire, the current building’s kitchen was rebuilt in the third year of the Bunsei era (1820). In the fifth year of the Tenpō era (1834), the old Jijuin Temple donated 170 ryō (roughly 60,000 USD) to rebuild the reception hall.

庫裏 「香積院」Kuri Kojakuin

The Zen temple’s kitchen has many gables. The entrance is on the gabled side. Its large gables and walls are particularly striking.

Attached to the abbot’s chambers, it is called “Kōshakuin” and is said to have been constructed in the 4th year of Bunka (1807). The grand entrance on the right side facing the front was set up in the sixth year of the Meiji Era (1883) on the occasion of the 500th anniversary of the death of Shōkokuji’s second Teacher of the Nation (Fumyō Chikaku). Until that time it was thought of as a worship space for Idaten (Skt. Skanda) Shōkokuji’s kitchen has a well balanced facade, and as a survival of the Five Mountain’s large scale kitchens, is important to national history.

This shrine was designated a Tangible Cultural Property by the Kyoto prefectural government in 2007.

承天閣美術館Jotenkaku museum

Shōkokuji Temple (official name: Mannenzan Shōkoku Shōten Zenji) was founded in the 3rd year of Meitoku (1392) by Soseki Musō. Established by the third shogun of the Muromachi shogunate, Yoshimitsu Ashikaga, it is the head temple of the Shōkokuji branch of the Rinzai school. Second in Kyoto’s Five Mountain System, it has contributed Zen monks such as Chūshin Zekkai and Keisan Ōsen that are representative of the Five Mountains Literature, as well as many artist monks such as Josetsu, Shūbun, and Sesshū who set the standard of Japanese ink painting. It remains at the heart of Kyoto, both geographically and culturally. Through this distinguished 600 years of history it has transmitted many cultural properties, particularly Zen writings, paintings, and tea ceremony utensils from the Middle Ages.

In the April of Shōwa 59 (1984), as a campaign of activities for the 600th anniversary of the establishment of Shōkokuji, works of art from Shōkokuji Temple, Rokuonji Temple (Kinkaku), Jishōji Temple (Ginkaku), and other sub temples and temples were entrusted to this newly established museum for preservation, display, repair, research, and the spread of Zen culture. It currently has an outstanding collection of cultural assets, including five National Treasures and 145 Important Cultural Properties and carries out various exhibitions.

The first exhibition room has a restoration of “Sekkatei,” a Zen tea house said to have been built on the grounds of Rokuonji Temple by Sōwa Kanamori. The second exhibition room has an installation of part of the masterpiece of ink painting and Important Cultural Property, the “Rokuonji ōjoin Shōhekiga,” a series of wall paintings by the rare genius of the Middle Ages Kyoto art world, Jakuchū Itō. You will be able to view works of art closely in the peaceful space of an ancient temple ground. We look forward to you viewing them.

Click here for details

豊光寺Hokoji

After the death of Hideyoshi Toyotomi in August of the third year of the Keichō era (1598), the 92nd abbot of Shōkokuji, Oshō Saishō Shōtai, constructed Hōkōji Temple for Toyotomi’s death anniversary services.

He joined Shōkokuji on February 19th of the 20th year of the Tenshō era (1584). In July of the 20th year of the Keichō era (1607), Ieyasu Tokugawa visited Hōkōji, but Oshō Saishō passed away on December 27th of that year. After this, Hōkōji was destined to fall into disrepair before being burned in the Great Tenmei Fire of the eighth year of the Tenmei Era (1788).

Oshō Ogino Shōshu lamented this destruction, and in the fifteenth year of the Meiji era (1882), it was merged with the sub temple Reikōkan and moved to its reception hall. In the 16th year of the Meiji era (1883), its kitchen, entrance, and other areas were rebuilt. In Meiji 19 (1886), upon receiving a donation from lay believer Gorobē Inōe for a secluded dwelling, it was turned into a writing room, given a small financial endowment, and rebuilt as Ichirikiji Temple

After the death of Oshō Ogino, in the April of the 32nd year of the Meiji era (1899), supporters of his studies had the “Taikōtō” (“Retirement Tower”) built. His epitaph was inscribed by Tessai Tomioka. Furthermore, Tessai’s calligraphy of the word “Zenrin” (“Good Neighbor”), which is hung in the entryway, transmits to us the heart of this Zen master, who admonished us to treat all people equally. Oshō Ogino’s book, “Zenrinsō Hōden” (“Story of a Zen Monk”) and his poems for his followers (held in the Jotenkaku Museum) have been handed down to us.

Hōkōji Temple’s main gate is broad with a cusped gable, with a style from the Momyama period or early Edo period. The pillars stretch up to the curved supports, conveying an old tradition from the Heian era.

開山堂庭園Kaizandoteien

Founder’s hall garden

![Founder's hall garden]()

As the name Founder’s hall suggests, it enshrines a wooden image of temple founder Teacher of the Nation Musō. It is to the east of the lecture hall and the most precious location on the grounds. In the first year of the Ōnin era (1467), it was burned by soldiers during the Ōnin War. In the sixth year of the Kanbun era (1666), Emperor Gomizunō reconstructed it for Imperial prince of Katsura No Miya and third generation Imperial prince Yasuhito, but in the eighth year of the Tenmei era (1788), it was once again burned down in the Great Tenmei Fire. In the last years of the Edo period, Monin Kyōrai, wife of Emperor Momozono, donated the grounds of the Kurogoden (the Black Palace) and the building was relocated there in the fourth year of the Bunka era (1807). It was expanded for use as a temple. The current form of the Founder’s hall is a normal level surface, with a worship hall in the front and a central hall for the mortuary tablets of lay believers.

An image of Teacher of the Nation Musō, founder of Shōkokuji Temple, is enshrined on the front side. On the western altar, images of Teacher of the Nation Bukkō, Teacher of the Nation Fukkoku, Teacher of the Nation Fumyō, and Yoshimitsu Ashikaga are enshrined. On the eastern altar, mortuary tablets and images of nobles with connections to Shōkokuji are enshrined.

The Founder’s hall’s south yard has a broad traditional dry garden covered in sand in the front. In the back is a gently sloping moss covered artificial hill. A small river about five shaku wide (about 1.5m) used to flow between them, but in the 10th year of the Shōwa era (1935), the water source dried up. This water was irrigation water that flowed south from Kamigamo, a stream flowing from the Kamo River to Kamigoryo-Jinja Shrine, to the Shōkokuji Temple grounds, to the Founder’s hall, to Kudokuin Temple, to the Imperial Palace gardens. For this reason, it was known in the temple as “Ryūensui” (“Imperial pool water”) and the water channel proceeding from the Founder’s hall was called “Hekigyokukō” (“Appearance of jasper”).

Shōkokuji Temple’s Founder’s hall garden is, strictly speaking, both a “mountain water garden” due to the artificial hill and flowing water and a “dry landscape garden” due to the garden stones arranged on white sand that create a link to the divine spirits of quarried stones. It is an interesting form that combines two styles in one garden and links two types of gardens into one form.

Musō Kokushi (Teacher of the Nation Musō)

![Musō Kokushi (Teacher of the Nation Musō)]()

Image height 114cm

When the Founder’s hall was first built, it was called “Shijuin Temple.” There was certainly an image of Musō Kokushi enshrined in it, but by the time of its establishment it had already been lost in a fire. It is not known when or in what era the current image was sculpted so it is impossible to say for certain, but it cannot be from any later than the middle Muromachi period. Accordingly, the image enshrined up until the reconstruction in the first year of the Bunshō era (1466) must be this one.

The image has a small and slim figure but it expresses the personality of the Musō Kokushi, the most intelligent and knowledgeable person of the era, quite well. It is said that his shoulders were so slim they gave birth to the phrase “Musō shoulders.” The image represents this very well with a monk’s stole that seems about to slim from his shoulders.

Wooden image of Sogen Mugaku (Teacher of the Nation Bukkō)

![Wooden image of Sogen Mugaku (Teacher of the Nation Bukkō)]()

Image height 93cm

A wooden image of the Musō Kokushi’s Dharma ancestor, Teacher of the Nation Bukkō (Sogen Mugaku). Sogen Mugaku was born in the second year of the Karoku era (1226), in the Chinese city of Mingzhou in Qingyuan. At the time of his residence in the north hall of Jinzu Temple in Hang Prefecture and entry into the priesthood, he was 13 years old. In the second year of the Kōan era (1279), he came to Japan in response to a request from Tokimune Hōjō. In August, he entered Kamakura’s Kenchōji Temple. In December of the fifth year of the Kōan era, he built and founded Engaku-ji Temple in the Jishu school of Buddhism. On September third of the ninth year of the same era, he passed away at age 61. This image was made on the occasion of Emperor Gomizunō’s reconstruction in the sixth year of the Kanbun era (1666), or perhaps a little later as a donation from the temple’s 100th abbot Myōjo Joshū. In any event, it was made by the Buddhist sculptor Ryōmu Hokkyō and enshrined on September third of the second year of the Enpō era (1680). On July seventh of the second year of the Tenmei era (1782), it was repaired by Buddhist sculptor Ryūkei Shimizu and escaped the Great Fire in the eighth year of the Tenmei era (1788) without harm.

Wooden image of Kennichi Kōhō (Teacher of the Nation Fukkoku)

![Wooden image of Kennichi Kōhō (Teacher of the Nation Fukkoku)]()

Enshrined on the left of Bukkō Kokushi is Fukkoku Kokushi, Kennichi Kōhō. Kennichi Kōhō is temple founder Musō Kokushi’s ancestor in the Dharma lineage.

He was born at the Imperial villa in Jōsai in the second year of the Ninji era. As son of Emperor Gosaga, he was an Imperial prince.

Towards the end of the second year of the Kōan era (1279), through the mediation of Serashūzōji Temple’s Ingō Ichō, he was introduced to Sogen Mugaku as soon as he arrived in Japan at Chōrakuji Temple.

In the third year of the Kagen era, the vestments received from Teacher of the Nation Bukkō were given to Soseki at Jōchiji Temple in Kamakura and he received his Dharma transmission.

Disciples in this Dharma lineage include, beginning with Soseki Musō, Myōjun Ōhira, Hongen Gennō, and Enkō Tengan. The Bukkō line was particularly prominent in founding the basis for the expansion of Zen temples in the Kantō region, along with the Daikaku line of Lanxi Daolong.

This wooden image was also donated by the 101st abbot of this temple, Kenrei Taikyo, on November 20th in the eighth year of the Enpō era (1680). As with the statue of Bukkō, it was carved by the Buddhist sculptor Ryōmu and is enshrined in the Enmyō Tower.

Wooden image of Myōha Shunoku (Teacher of the Nation Fumyō)

![Wooden image of Myōha Shunoku (Teacher of the Nation Fumyō)]()

眞如寺Shinnyoji

In the Kamakura period, as the elder nun of Keiaiji Temple (one of the Five Mountain Nunneries of Kyoto) Muchaku Nyodai Oshō was nearing the end of her life, she created a cemetery at the foot of Mt. Kinugasa to enshrine the remains of her Dharma teacher and founder of Kamakura’s Engakuji Temple, Bukkō Kokushi (Zen Master Sogen Mugaku). The cemetery was named Shōmyakuan, and she protected it until the end of her life. After Nyodai Oshō passed away, Shōmyakuan was on the verge of breaking down. Musō Kokushi, as Bukkō Kokushi’s Dharma successor, received support from Shogun Takauji Ashikaha’s regent, Kō no Moronao and Takauji’s younger brother, Tadayoshi Ashikaga, to build a massive, fully equipped temple complex around the remains of Shōmyakuan. It was named “Shinnyoji Temple,” after Bukkō Kokushi’s home temple of the same name in Zhejiang Province, China. Bukkō Kokushi was made the official founder of the temple and Nyodai Oshō was made the official founder of the building. Musō Kokushi entered the temple as the second abbot. As third highest-ranked in the Muromachi period Five Mountains and Ten Monasteries System, the Musō lineage received support for its development, but due to the Ōnin War and other disturbances it began to fall into disrepair. At the beginning of the Edo period, it was revitalized by Emperor Gominō. Under the Five Mountain Schools system, it became the head of the training temples and its lecture hall was used to hold Dharma transmission ceremonies.

慈照院Jishoin

Around the 12th year of the Ōei era (1405), the resident Zen master (13th abbot of the Shōkokuji Head Temple) began constructing a temple complex called “Daitokuin.” In the end year of the Entoku era (1490) it became the resting place of Yoshimasa Ashikaga and was renamed “Jishōin” by imperial decree. Yoshimasa’s posthumous Buddhist name was “Jishōin Denjun Sannomiya Sōdai Shōkoku Ippin Kizan Dōkyō Daizen Jōmon,” and the incident was recorded in detail in Shūrin Keijo’s autobiographical work, “Daitokuin Kaigōki” (“Record of the renaming of Daitokuin”). His grave is in Shōkokuji Temple’s graveyard.

In the sixth year of the Kan’ei era (1629), during the time of Busshō Hongen Kokushi, seventh abbot of thie temple (birth name Kentaku Kinshuku), First Generation Imperial prince of the Katsura No Miya Toshihito built a school for the Imperial family within the grounds of this temple complex in deep consultation with Second Generation Imperial prince Toshitada. The school was bestowed on Oshō Kinshuku in the ninth year of the Kan’ei era (1632). Currently known as “Seihekinoki,” its architecture is after the fashion of the ancient book archives on the grounds of Katsura No Miya palace. The building materials are all early Edo period, mimicking the appearance of a thatched hut.

Oshō had intimate friendships with Urakusai Oda, Shōan Sennō, and Sōtan Senno. The tea house was built by Sōtan and was called “Ishinshitu.” After its completion, Sōtan would often come for tea ceremonies. Therefore, it is known as “The Tea House that Sōtan Loved” in the legend “Sōtan the Fox.”

Afterwards, in the 11th year of the Kanbun era (1671), Tokugawa Owari built the current main hall in accordance with the dying instructions of Imperial prince Toshihito Hijōshōin. It was made into the mortuary tablet hall of the Katsura No Miya family. In the fourth year of the Hōei era (1707), Emperor Higashiyama donated a sanctuary. In the 13th year of the Hōreki era, the old Katsura No Miya hall was given an expansion. The Hirohata family remodeled the entryway.

After the Great Ōnin War, it managed to avoid both the fires of war and natural disasters, gradually expanding and flourishing as a temple.

Currently, the temple holds many important works of art that are important cultural properties. These include four-legged ash glazed urns (Heian period), colored silk images of the 28 legions of protective deities (Kamakura period), colored silk images of Jizō Bodhisattva (Nanboku-chō period), the record book of the court mourning for Jishōinden (Muromachi period), and paper and ink images of Daruma by Bokushō (Muromachi period). It preserves items related to the Imperial family, paintings and calligraphy from the Korean delegation to Japan, and personal effects of Yoshimasakō Ashikaga.

慈雲院Jiunin

Built in the Chōroku era (1457-59), the main object of worship is Shakyamuni Buddha.

The founder was the 42nd abbot of Shōkokuji Temple, Zen master Kōshūmeikyō Chokushi (Oshō Zuikeishūhō). The master was also a great scholar of Confucianism and prolific author who combined reverence for the emperor with faith in the shogunate. The second abbot, Oshō Mokudō Toshiaki, revised the hymns of Shōkokuji Temple, the music of which has been transmitted to this day. Even among these, “Kannon Senbō” is the foremost and a particular point of pride.

Entering the Edo period, ninth abbot Oshō Baisō Kenjō overwhelmed the era with outstanding poetry and won the confidence of the shogunate. He was heavily involved with diplomatic papers as an official secretary of Korean documents and was briefly an advisor of the shogunate. The master devoted himself to the revival of Shōkokuji Temple after the Great Tenmei Fire (1788) and accomplished its reconstruction.

In addition, he was the mentor of the brilliant painter Ito Jakuchu, who left behind many works, including the series of thirty-three paintings titled “Dōshoku Saie” (“Colorful Realm of Living Beings,”) among others. Their relationship was vely close.

Jiunin Temple was originally on the site of Kyoto Sangyo University Junior & Senior High School, but in the 29th year of the Meiji era (1896), it was demolished and the name of temple was changed to Fushunken.

In the Taishō period, the 15th abbot Oshō Takudō Shūkei encouraged social activities, promoting “one day, one good deed.” In the sixth year of Taishō (1917), he published the magazine “Shūzen.” In the 13th year of Taishō (1924), he established the Wakei Gakuen school, which remains to this day.

法然水Hounensui

Before the establishment of Shōkokuji Temple, Pure Land school founder Hōnen Shōnin (St. Hōnen) revered the god Kamo Myōjin while living at Jingūji Temple on the Kudokuin Temple complex. Due to this, he made a pilgrimage to Kamo Shrine. Seeing the beautiful, clear waters of the garden lake of this combined shrine and temple, Hōnen Shōnin composed a song for himself about that complete clarity.

Shōkokuji Temple was later constructed on the remains of that combined shrine and temple. The lake is now a well known as the place where Shōnin drew the “Akasui” (“Waters of the Buddha”). There is a memorial monument and the town to the north gate is known as “Hōnensui” (“Waters of Hōnen”).

After the death of Hōnen Shōnin, his disciple Genchi Seikanbō Shōnin built a memorial hall for him during the Kenpō era in gratitude for his master’s virtue. It was named “Chionji Temple.” After a number of changes of location, it was moved to the the grounds of Hyakumanben Temple. This temple is now known as “Hyakumanben Chionji Temple.” In gratitude for their relationship with Shōkokuji Temple, they send an invitation every year for the anniversary ceremony of their founder’s death.

The Waters of Hōnen are an important historical site that shows the deep relationship between Shōkokuji Temple and Hyakumanben Chionji Temple.